Shipping calculated at checkout

about the book

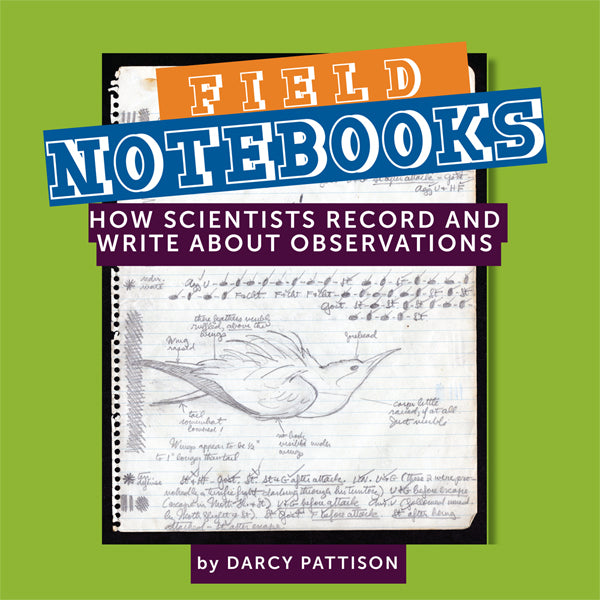

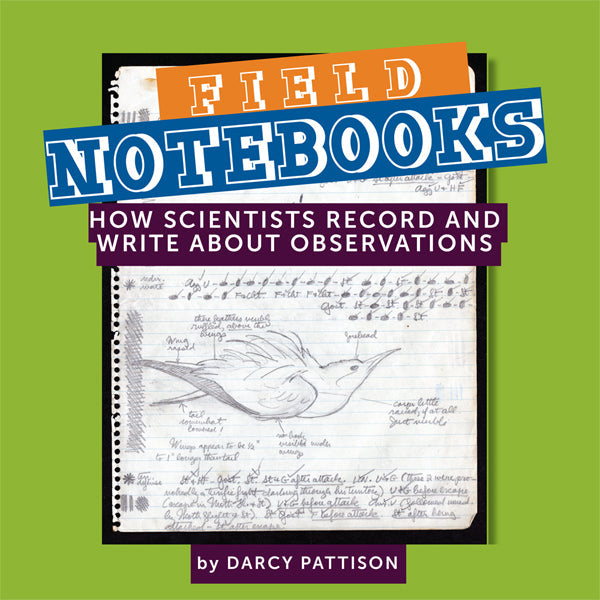

- by Darcy Pattison

- Photos

- 8.5" x 8.5"

- 32 pages

- 920L

BIOGRAPHIES OF SCIENTISTS + THEIR SCIENCE OBSERVATION NOTEBOOKS

Put scientists out in the field—where they observe and learn from their subjects—and exciting things happen.

“…provides clear, understandable, but not oversimplified explanations in an attractively presented format. The notebook entries make for compelling study…” Kirkus Reviews

Join fourteen American scientists as they watch sleeping hippos, avoid cactus thorns, hide snakes under their skirts, make jokes, and draw elephants, termites or squids. Drawing from the original field notebooks of scientists, kids will learn about descriptive, informative, humorous, and expository writing. Scientists use notebooks to summarize data, draw maps, or draw specimen.

Represented are scientists studying

- birds

- cactus

- zoo keeping

- human diseases

- termites

- mollusks

- fish

- grasses

- Mayan ruins

- Chinese plants and animals

- taxidermy

- peanuts.

Kids will be inspired to create their own field notebooks. The work is presented in a fun, browsable layout. Any time you want to pair observations with recording those observations, this is the right book.

17 Things That Should Be Included in a Science Notebook! What to Write in a Notebook!

Teachers and parents often ask what a child could put in a science notebook. After studying actual scientists' notebooks, here are 17 common things included:

- Name. Include the observer's name.

- Date. When was this observation made?

- Location. Where was this observation made? This could include something complicated like GPS coordinates, but it's fine to just include a short description such as "Lakeside Elementary playground," or "My backyard."

- Lists. The easiest and most common writing in science notebooks is a simple list. This may be a list of birds seen in a month, or a list of equipment.

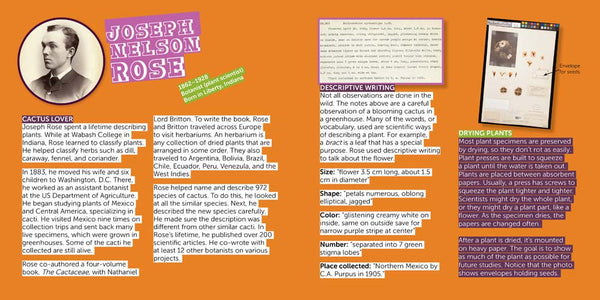

- Descriptive Writing. Science notebooks often describe the thing being observed. It includes visual, auditory, tactile, smell, and, if appropriate, taste details. The sensory details are supported with measurements of weight, size, shape, number (example, number of lobes on a leaf), and the place collected.

- Specimen. Often a scientist will insert a specimen, when appropriate. This may be a dried leaf from a plant, or a photo of an insect.

- Narrative Writing. When a scientist goes into the field, it is a journey. They often document the trip in a narrative style, explaining what they do each day. This diary-like entry included sensory details, information on events, location details, and personal opinions.

- Humor. Over and over in the scientist's notebooks humor finds a place. The scientists are able to step back from their studies and find funny moments to chronicle.

- Hand-drawn illustrations. Scientists often use drawings to record details about their studies. This may be a detailed drawing of an octopus from three different perspectives, or details of a bird's wings.

- Photography can't replace this because the illustration can show the same object from various positions. Also, scientists will label and make other notes on the pages.

- Repeated Observations. Often scientists return to the same location to repeat observations. They may repeat observations at different times of the year, or different rain conditions. One scientist watched two termite colonies fight and recorded observations at the beginning, 15 minutes into the fight, and 30 minutes into the fight.

- Labeled Drawings. Drawings often need labels to explain what is shown. For example, one scientist drew three native potteries. The label explained that one was the size of a cup, one held about two quarts, and the largest held about five gallons. Without the label, the relative sizes of the pots would not be understood.

- Color Illustrations. Extra information is often added with color. In one scientist's notebook, two similar fish were distinguished when color is added. Close-up Illustrations. Illustrations in a science notebook may be life-size, or may zoom in close. These close illustrations allow scientists to add extra observations and details.

- Landscape illustrations. On the other hand, when a scientist wants to place observations in context, the strategy may be to draw a landscape. When the viewer's eye is pulled out to this wider angle, the observations are clearer in context.

- Informative Writing. Often a scientist writes in an informative manner, conveying information about his observations. These are detail-oriented and meant to inform the reader. Interestingly, the scientist is often the reader, as they re-read their notebooks before reporting their observations.

- Diagrams, Charts, or Maps. When needed, scientists add explanatory drawings. They chart, diagram, or map as they observe.

- Photographs. Today, scientists often include photographs as part of their notebooks. These could be close-ups, landscapes, or even x-rays.

- Writing Prompts After reading about a scientist and how each wrote in their journals, it should be easy to create writing prompts. Think about how the scientist used the writing to record information, data, or humor. Read this book for a deeper understanding of famous scientists and their notebooks.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

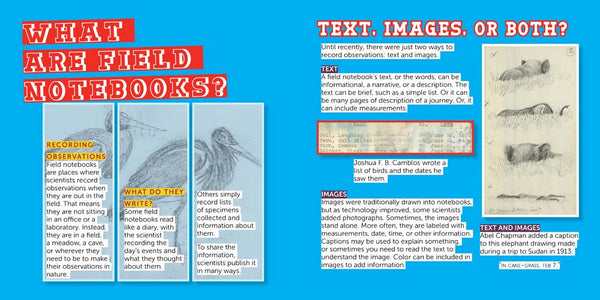

- What are Field Notebooks?

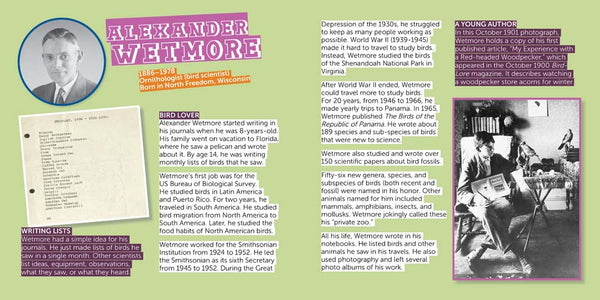

- Alexander Wetmore, ornithologist

- Joseph Nelson Rose, botanist

- Bill and Lucile Mann, zookeeper and writer

- Fred Lowe Soper, epidemiologist

- Martin Moynihan, ornithologist

- Margaret S. Collins, entomologist

- William Dall, malacologist and naturalist

- Donald S. Erdman, ichthyologist

- Mary Agnes Chase, botanist

- William Henry Holmes, anthropologist and artist

- David Crockett Graham, missionary and naturalist

- Watson M. Perrygo, taxidermist and exhibits specialist

- George Washington Carver, chemist and agriculture professor

- Start Your Own Field Book